Single Shot at Doctor's Office May Be Future of HIV Prevention

- Author:

- NBC

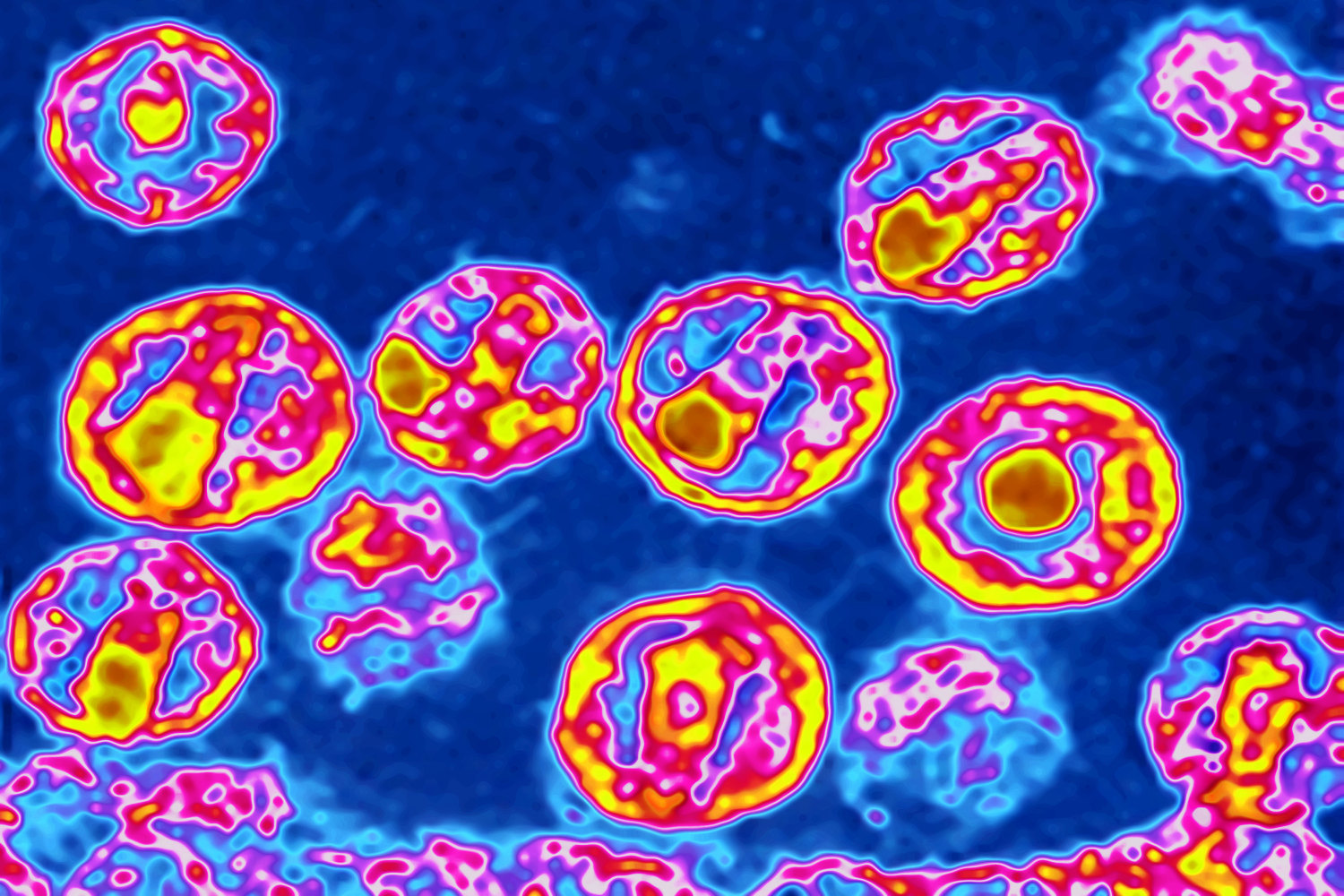

HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. Photo: BSIP/UIG Via Getty Images

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced last week that it was entering the first-ever global clinical trial of an injectable HIV-prevention drug called cabotegravir. The trial is taking place in eight countries across three world regions—the Americas, Africa and Asia—and researchers are enrolling 4,500 gay and bisexual men along with transgender women, pulling from groups with the highest rates of new infections.

"The annual number of new HIV infections among young people, especially young men who have sex with men and transgender women who have sex with men, has been on the rise despite nearly flat HIV incidence among adults worldwide," said Raphael J. Landovitz, the Protocol Chair for the study.

In the U.S., the Centers for Disease Control reported new HIV diagnoses have declined by nearly 20 percent—mostly among white gay and bisexual men. But HIV rates are on the rise for men of color and transgender women, as well as youth. Data suggests the disparity might be due to Truvada itself: A 2016 study found 74 percent of Truvada users were white, and the number of black users dropped between 2012 and 2015.

Patients participating in the new study will be randomly assigned to receive Truvada pills or cabotegravir injections, to compare the injectible drug's efficacy with the established PrEP pill. Currently, Truvada is the only commercially available pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) medication, and the only FDA-approved HIV-prevention method, period.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the NIH, told NBC Out the hope is the injectable PrEP drug will work as well as Truvada—which currently has a roughly 99 percent rate of success in preventing transmission of the HIV virus.

"The ultimate reason for the trial is that many people who take Truvada have difficulty with having to take a pill every single day," Fauci said. "That really becomes prohibitive, and sometimes people don't adhere really well."

Fauci explained that while it would be ideal for patients to only have a shot once a year, for example, the 8-week period is how long cabotegravir stays in the system inhibiting the virus from taking hold. If the current trial is successful, he predicted, researchers will likely begin to tweak the drug's chemical makeup in an effort to make it last longer.

Full results of the trial are expected by 2021 but could come even sooner. A related trial testing the injections on cisgender young women is slated to begin in 2017.

The stunning efficacy rates of Truvada have launched a race to expand the market. Researchers are currently studying an HIV vaccine that uses antibody injections, a microbicide gel that can be used as a sort of HIV-prevention lube and a slew of other HIV drugs for treatment and prevention.

Damon Jacobs, an HIV-prevention specialist who moderates the 15,000-member Facebook group PrEP Facts: Rethinking HIV Prevention and Sex, told NBC Out the plethora of future prevention methods looming on the horizon is "wonderful."

"It's not going to be one size fits all," he said. "Just like with birth control: some women take the pill, some get an IUD. I'm glad we're going in that direction for PrEP as well."

According to Jacobs, the PrEP race in medicine is happening because of Truvada's runaway success. While the studies showed Truvada prevents HIV transmission at near-total rates, it's only over the course of the past couple years that the wider effects have been seen. Truvada was introduced commercially in the U.S. after its FDA approval in 2012—since then, New York City has announced new HIV rates fell below 2,500 for the first time since the epidemic exploded in 1981. Jacobs said PrEP was largely responsible for the decline.

"We're seeing how well it works for communities when there's wider implementation and access," Jacobs added. "We're looking at areas where the use of PrEP is being validated by local governments—subway ads, newspaper ads, doctors being supportive of it."

There are still kinks to be worked out when it comes to PrEP. Truvada is expensive, and some communities—particularly gay and bisexual black men, who are at the highest risk for new infections—report frustrating experiences with doctors reluctant to offer PrEP medication. And within the gay community, critics suggest some men may be overly reliant on PrEP alone, rather than using condoms in addition to the drug.

But Jacobs said condoms and PrEP aren't an either-or scenario. Truvada, he said, is filling the space that was left empty years ago in terms of HIV prevention.

"Even when the consequences of not using condoms was death, people weren't using them," he said. "Why would you think they're going to start using them now?"

New drugs like cabotegravir are poised to fill even more gaps. One early study of Truvada (the "iPrex" trial) showed that while 93 percent of study subjects reported taking the daily pill, only 51 percent actually kept up the regimen. For patients who don't adhere well to daily medication, a shot every two months is a highly desirable alternative.

For Jacobs, who works as a marriage and family therapist in addition to educating people about PrEP, the expansion of HIV-prevention methods is a boon not only to the health of Americans, but also to their emotional and sexual wellness.

"People are having sex for pleasure, to experience intimacy and connection with a partner," Jacobs said. "These studies are beautiful, because they will allow more people to connect in meaningful ways."

by