A generation of artists were wiped out by Aids and we barely talk about it

His life was an artwork … Robert Mapplethorpe. Photograph: Leee Black Childers/Redferns

There are many shocking images in the brilliant new documentary Robert Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures, made by Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato. You probably know many of them already. Some are just seared into our culture and no longer disturb anyone. The cover of Horses with Patti Smith was as much of a statement as her music. His celebrity pics of Eurotrash and rich collectors, or actual celebs such as Debbie Harry and Bianca whispering in Mick Jagger’s ear remain fascinating. Their beauty blasted by his light into timelessness; his naked flowers, the sex organs of plants in all their glory. As he said himself, he could perfect a bowl of carnations just as well as “a fist up someone’s ass”. Then there was the documentation of his S&M activities and his fetishisation of the black body – so many of these images remain, to use the worddu jour, “problematic”. Good. His life was an artwork. He would pick up guys, do drugs, have sex and then get down to work. He would photograph them.

When you see these pictures, you wonder why – with sexual imagery everywhere all the time – these pictures linger, hanging somewhere in a dark part of the collective memory. You keep looking because he kept seeing.

In this film, we have Mapplethorpe in his own words, not the rose-tinted memories that Smith gave us in Just Kids. He is openly a man of sociopathic ambition who wants sex, fame and money, and would use anyone to get them. That countercultural drive echoed what was going on in the 1980s so much that it would become indistinguishable from mainstream culture. When people talk about the end of the New York scene, that’s what they mean.

Just as he got what he wanted, he got sick. This “ruined Cupid”, this beautiful man, we see skeletal with Aids giving his final party.

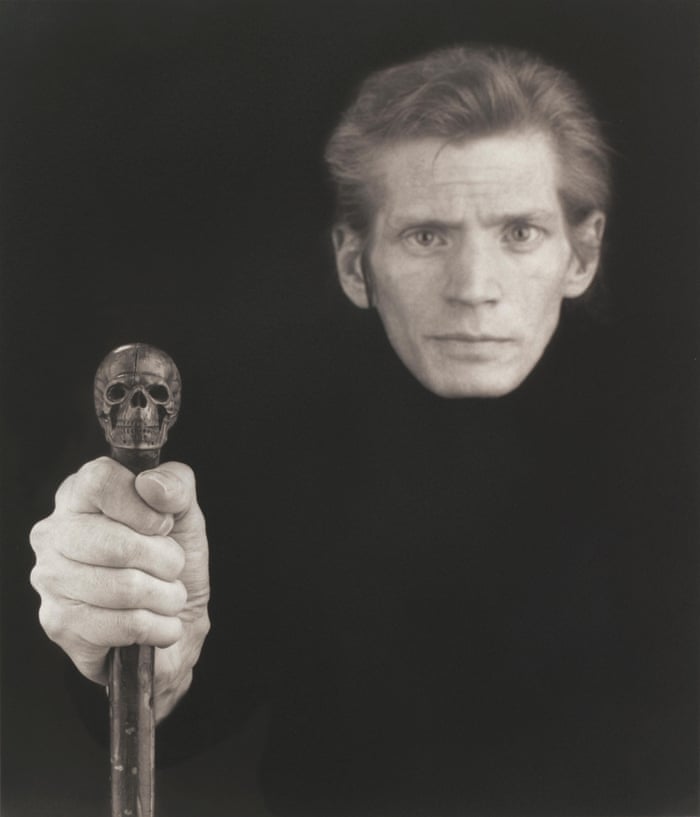

“Whether it’s an orgy or a cocktail party I know how to do it.” He certainly did. It’s hard to see this vain man visibly dying. But he made his death part of his art. His1988 self-portrait with a skull cane remains a masterpiece. I feel sorry for those who say photography is not an art. Bowie used his death in his final work too. No hiding away.

But what the film also brings home is the erasure of history – the fact that all those deaths from Aids have been somehow glossed over. Gay people can get married. Everything is lovely now!

It’s hard to see this vain man visibly dying … Mapplethorpe’s 1988 self-portrait with skull cane. Photograph: By permission: Mapplethorpe Foundation

Yet there was a time when you could walk around London or New York and see these gaunt faces, marked with sarcomas, and everyone you hung out with was dying. The official culture was in denial. Sometimes it was easier to be. I remember seeing Derek Jarman at a play. At that point he was blind. I didn’t want to see him like that. And then my friend was queer-bashed on the way home.Freddie Mercury died. Keith Haring died. Eazy- E from NWA died. Denholm Elliott died. Rock Hudson died. Fela Kuti died. And my uncle who wasn’t famous or even my actual uncle died. One of my friends lost seven people who were all under 30.

I was explaining this to my 25-year-old daughter. She understood what happened, but said, “I just can’t imagine it”. And somehow nor can I, but we lived through it. HIV, we say, is now no longer a death sentence. But, of course, it is in many parts of the world. South Africa has a 19% HIV rate. Russian is only just starting to admit the scale of its problem with an estimate of 1.5 million people with HIV. Neither homosexuality nor addiction can be spoken about in Putin’s Russia.

Mapplethorpe’s work was censored by US senator Jesse Helms who, like many Republicans, saw Aids as a punishment for homosexuality. Nancy and Ronald Reagan pretty much signed up to this line. Republicans banned needle exchanges. The Catholic church banned condoms. Mapplethorpe’s work is shot through the lens of his Catholic upbringing, the black mass and rituals of S&M – his composition, his invocation of the devil not as a metaphor, but as a living presence.

He was but one of a generation of artists, activists and athletes wiped out by Aids. Why don’t we speak about this anymore? Is it ancient history? Not for me, as it propelled a politics of queer solidarity arising from horrific circumstances.

The debate about safe spaces came to mind watching this film. Mapplethorpe’s entire oeuvre was a trigger warning. A bullwhip up his rectum, a penis lit like Mona Lisa. He died at 42.

When Paul O’Grady was asked in the Guardian about the death of his friend Cilla Black, he said: “I’ve lost about everybody I know.” He talked about Aids wiping out all his friends, and about having to pretend to some of their families that they were dying of cancer as he nursed them. “People my age will never get over the horrors.”

Antiretrovirals may make us think it has all gone away. It hasn’t. Aids is killing people all over the world. The living death mask of Mapplethorpe disturbed me more than any pictures of fisting. Because I thought of all those we lost, and how we don’t really want to remember any more. Mapplethorpe’s unblinking need to document his life, his sex, his magic and his death reminded me why we must never forget. The battle is not won.